We Get Around

Tiquipaya - April 2024

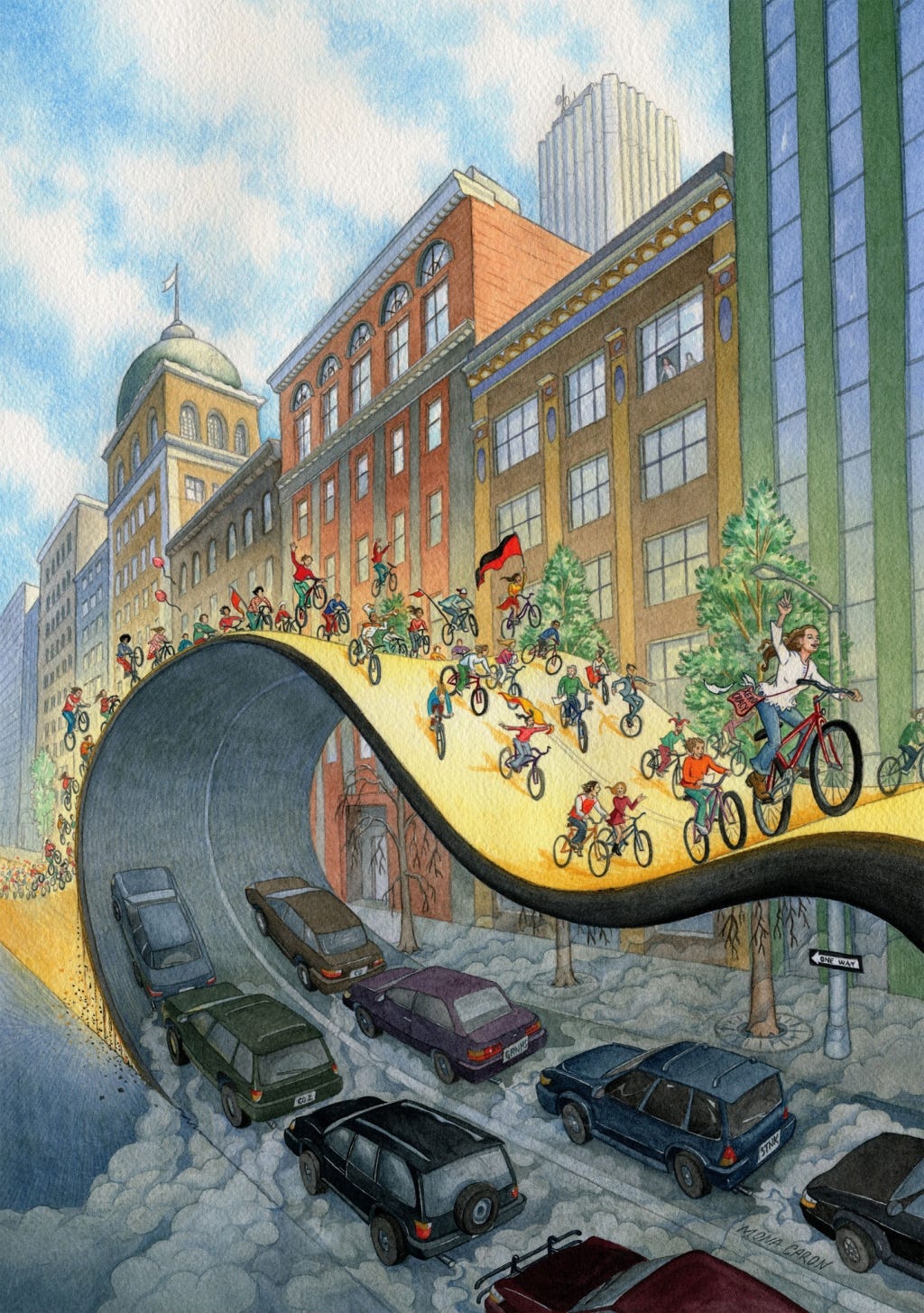

Yesterday was Día del Peatón—Pedestrian Day—when all of metro Cochabamba valley, with its ~1.5 million inhabitants, is free of motor vehicles and the streets are full of people on foot, bike, roller skates, scooters, strollers and all manner of baby cars. We walked from our home at the foot of the mountain to Tiquipaya town’s plaza, and instead of taking our usual back-street dirt-and-cobbled route, we took the main paved avenue, a 20-minute walk downhill. With the street blissfully clear of cars and trucks, birds sang the praises of the air flowing clean and quiet, and children, youth, adults and old folks were all strolling, cruising along on people-powered wheels, or just standing in the middle of the road. As usual, food was being served on the sides of the road, and today there were more than the usual small clusters of people eating and drinking at tables laden with huge mounds of food. Grills smoked and frying pans sizzled on the sidewalk, pots steaming as they were carried full from the cooks’ gardens and homes that peek behind the walls lining the road. As Mwende and I moseyed along, the kiddo cruised on her little low-to-the-ground “avión” car. We passed other full gardens: patio parties and chicherías blasting reggaetón and Andean folklore. The regular Sunday market was buzzing downtown, with all its usual color and sound and smells of homemade food brightened by the absence of motor noise and exhaust that usually filters in. The plaza was hopping with blow-up jump houses, inflatable slides, trampolines and potato sack races for the kids, as well as tether ball and quizzes with saplings as prizes for the adults.

This morning Mwende was remarking how perhaps the most remarkable effect of this experience was in the body. She was surprised to realize how calm and relaxed she was in the street with our child—without the need to fear that one of us might be killed by a car. In the US there are virtually no urban public spaces or community moments where we can be safe from cars, and the feeling when you are set free of that fear and danger is exhilarating and an enormous boon to the nervous system.

Since our arrival last July, this is our third Día de Peatón—officially Día del Peatón y del Ciclista en Defensa de Madre Tierra—but most people drop the too-longly wonky and widely understood last part. There are usually three local Cocha Días de Peatón and one national Día per year. In Bolivia, the day started here, and has since spread to other cities nationwide. Worldwide, there’s precedence reaching back to the 19th century in England, and here in South America Bogotá famously has had their Bike Paths since 1974, where currently 128km of major avenues are reserved for bikes and pedestrians on every Sunday and holiday.1 In California, the closest thing I know of is in San Francisco, where during the pandemic they first opened up and then have maintained a car-free walk- and bikeway on weekends along a short stretch of the Pacific coast on Highway 1.2 Throughout the US, Critical Mass and others have been successfully campaigning for bike lanes and other bike rights, yet nothing of this scale that I’m aware of has been achieved… yet, let’s hope.

On our first Día de Peatón, which we enjoyed in Cochabamba city strolling about with my dad, we were blown away at the scale of festivities and the transformation of the city—unlike anything I’ve ever experienced. With mobility reduced, people stay very local, within reach of where our bodies can take us, and completely surrounded by our neighbors. Most work for most people becomes impossible, since so much of our labor requires fossil fuels to move us and materials across vast distances, and so it is a day of leisure and relaxation, of doing less and being more. We are dreaming of how we might bring this to our neighborhood in Richmond, where we live a few blocks from the all-but-abandoned Civic Center Plaza that we would love to fill with life; we can imagine our streets filling with neighbors, food, games, rest and non-productive joy.

One of my favorite aspects of living in the Andes is the myriad modes of transportation and the extraordinary flexibility of ways to get around. Working our way up from people’s amazing capacity walking,3 people mostly get around in cities on: motorcycle (often mototaxis), taxis (including apps), trufis (busses ranging is size from car to minibus/minivan), micros (the badassly painted oldschool-bodied bohemoths4), and in La Paz, the big urban Puma Katari busses that North Americans seem to think are the only viable mode of road-based public transportation, as well as the extraordinary teleférico (see my previous post on this wonder of the urban world). All of the above, except the La Paz big busses and teleférico, are privately run. How would our lives change in the US if we were able to flexibilize and diversify our mass transportation, whether public or private?

In our neighborhood here in Montecillo, we are right on the edge of the mountain, where town meets countryside, and there are four trufi minibus lines that come by, some going to town and some to the city, and usually we have to wait no more than 10 minutes to catch a ride that costs at most 2 bolivianos or 25 cents—cheap enough for just about anyone to access on the daily, even here. This is typical here: despite higher levels of discomfort and certain types of danger, I would take Bolivia’s transportation system of the US’s in a heartbeat. In our neighborhood in Richmond, California, at the edge of the high-tech hub of SF and Silicon Valley, and a stone’s throw from City Hall, there are only a handful of bus lines that come by, but the frequency and connectivity is so poor that for most it isn’t a viable option. If we were to split each of those huge busses into 4 small busses, might we have better coverage and flexibility? If we were to encourage private companies to have small bus-type lines instead of just app-based individual taxis, what might happen? When normal circulation is disrupted (think, pandemic, earthquakes or other disasters), this type of flexibility goes from helpful to vital; to become more resilient, to revitalize our peripheries, to care for our Mother Earth, and to make our lives better, we need to rethink our mobility. Bolivia is a great place to consider for some beautiful alternatives.

https://www.idrd.gov.co/recreacion/ciclovia-bogotana

https://sfrecpark.org/1651/Great-Highway-Hours-and-Schedule

More than anyone I’ve ever encountered, people in the Andes can really move on foot. I’ll never forget tromping around the Apolobamba mountain range with Don Mario Yanahuaya, outside of his town of Kaata, and experiencing the distances that he walked daily to his fields, or to gather herbs, or to visit relatives in nearby ayllus. I realized that a man of his community could quite easily walk to Panama within a couple of years. And indeed, the Kallawaya communities he is part of traditionally and famously send their healers out to walk the entire length of the Andes, and their height, gathering medicine from the tree line down to the Amazon, healing as they go. These were the healers the Inca chose, and they are known to have practiced successful brain surgery as early as 700AD.

On a more daily level, walking in the high Andes you’ll find local folks taking the many miles and astounding altitude in stride. Just ask them how far it is to get somewhere that will probably take you a day at least, and the answer will often be “aquicito no más”—“it’s just right here.”

These hulks definitely need better maintenance for safety, and smog regulation for easier breathing. I think a healthy balance might include more regulation here, and more flexible regulation in the US (of transportation, housing, food service and production, building, and so many other things).

Fantastic article. Do you post these of Medium?